One of the best parts about being a biological anthropologist is having the opportunity to travel to natural history museums all over the world and to see the collections that rarely, if ever, go on display to the public. Sometimes these hidden collections are pretty standard (imagine rooms full of skeletons…), but other times you come across scientific treasures, or just plain funny and unexpected things.

For the past two years, a couple of colleagues of mine, Siobhan Cooke from Johns Hopkins University and Claire Kirchhoff from Marquette University, and I have had the privilege to visit multiple natural history museums for our National Science Foundation funded research. Since January 2017, we’ve visited the

Field Museum, the

Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History,

Arizona State University, the

Cleveland Museum of Natural History, and for a month this past summer, we worked at the

Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium. It’s a rough life, but someone has to live it.

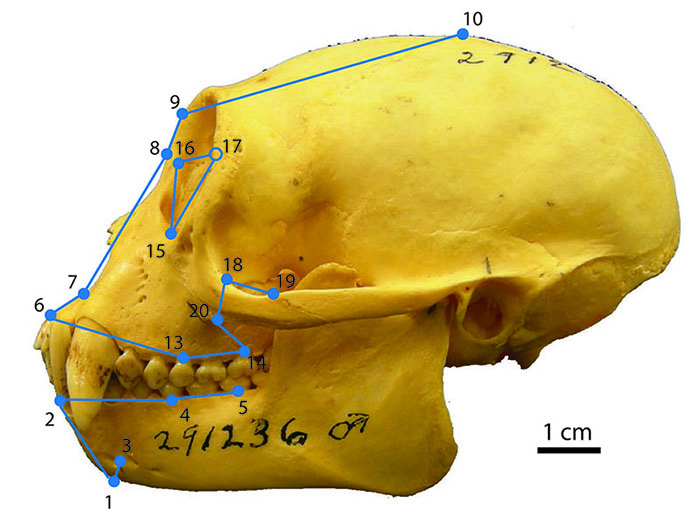

The idea for our research is this: on average, humans have pretty messed up jaws and teeth*, so what about non-human primates? We’re examining tooth shape and wear, the shape of the skull, and looking at pathologies that these primates have, all with the ultimate goal of trying to understand how our masticatory (or chewing) system functions as a whole both in humans and non-human primates, and especially trying to figure out what happens when things go wrong with our teeth or jaws. For example, do primates that have a lot of broken or missing teeth tend to have higher rates of osteoarthritis in their jaw joint? What’s exciting about this is that most of the time researchers try to focus their work on skulls that look the nicest. In other words, many scientists (myself included, at least in the past) try to only include specimens that don’t have missing teeth or healed fractures or osteoarthritis. But we WANT to look at these skulls, which we’re affectionately calling #MessedUpMammals. And oh my, are there lots of messed up primates that we’ve been coming across in our travels! It turns out that, at least in some primate species, they’re just as messed up as humans are, and our data are starting to suggest some interesting patterns showing relationships between tooth loss and joint problems.

Right now we’re at the point where we’ve collected a lot of data but haven’t analyzed it all yet, so stay tuned for more updates on our travels and results of our work. And of course, no one can work 24/7, so our travels also get to include some goofiness and of course many local culinary delights- just another reason that traveling for research is so much fun.

We are so grateful to the National Science Foundation (and tax payers like you!) for supporting this research (NSF BCS-15511766 (to CET), NSF BCS-1551722 (to CAK), NSF BCS-1551669 (to SBC)). If you have questions about this blog post or about our research more generally, don’t hesitate to email cterhune@uark.edu.

*While the National Institutes of Health reports that 5-15% of contemporary Americans experience symptoms related to jaw joint dysfunction (1), the rate of osteoarthritis may be as high as 85% in elderly females (2), and historically has affected ~40% of individuals in some contexts (3,4). Similarly, some estimates suggest that 70% of people will experience tooth loss within their lifetime (5), including 40% of Americans (6). But little to no comparable data are available for non-human primates.

References

- https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/facial-pain/prevalence

- Nicolakis, P., Burak, E. C., Kopf, A., Piehslinger, E., Wiesinger, G., Fialka-Moser, V. 2001. An investigation of the effectiveness of exercise and manual therapy in treating symptoms of TMJ osteoarthritis. CRANIO 19, 26-32.

- Hodges, D. C. 1991. Temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis in a British skeletal population. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 85, 367-377.

- Richards, L. 1988. Degenerative changes in the temporomandibular joint in two Australian aboriginal populations. Journal of Dental Research 67, 1529-1533.

- Marcus, S., Drury, T., Brown, L., Zion, G. 1996. Tooth retention and tooth loss in the permanent dentition of adults: United States, 1988-1991. Journal of Dental Research 75, 684-695.

- Hand, J. S., Hunt, R. J., Kohout, F. J. 1991. Five-year incidence of tooth loss in lowans aged 65 and older. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 19, 48-51.