Freshman Alice Stubbs recently joined the Terhune Lab as an undergraduate researcher. In this blog post she describes what it’s like to find a research lab to work in and what her lab duties are. Welcome to the lab Alice!

You may be wondering what’s it like to do undergraduate research in a brand new lab at a school you’ve just started going to. There’s a lot to learn and a lot to share with others about what it’s like to work in a university lab. From being a professional and intuitive environment, to being welcoming and open-minded about all things science, the lab experience can seem overwhelming at first. But, don’t worry! You are not alone. When I first started working in the Terhune lab, I was intimidated too. I quickly learned, however, that labs are amazing, fascinating, informative, and most importantly, it’s a new place with new experiences for any one who is interested! There’s always something to look forward to, and always more to learn.

Why should you join a research lab? It’s an extremely positive thing to do, as you’re constantly learning things faster than other people, in a specialized field. You have to have a thirst for knowledge, much like I did, and be ready to push yourself to new heights. Personally, I have loved anthropology since I started watching Bones at 14. Forensics was my favorite class in high school, immediately followed by anatomy. These classes allowed my interest to bloom and grow, and because the conditions of decomposition don’t bother me, I was able to feed my need for knowledge.

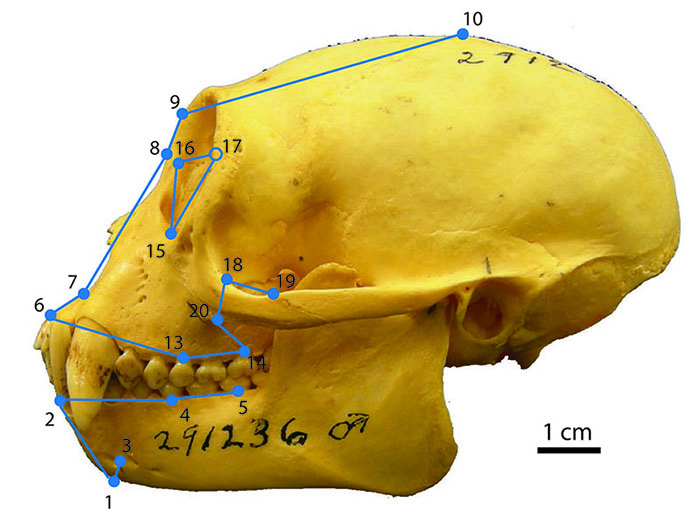

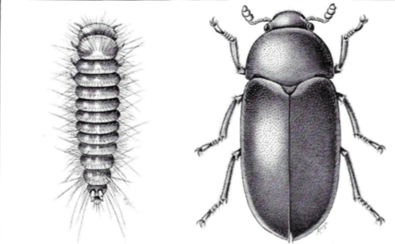

In the Terhune lab, my job consists of a lengthy, but interesting process that’s focused on taking care of the lab’s dermestid beetle colony. Dermestid beetles, also known as skin beetles, are important parts of the ecosystem, since they are some of the insects responsible for removing decaying tissue from carcasses and recycling nutrients back into the environment. They’re often used in forensic investigations to figure out time since death. Dermestid beetles are also used in museums and labs across the world to clean off skeletons so that the bones can be used for teaching and research. For my work, I have to come in at least four hours early and set out a carcass (in my case, lemurs that died of natural causes) to defrost. After the animal has had a few hours to thaw, I use a scalpel blade to remove the skin. I then work to remove as much skin as I can from the hands and feet, and then separate the hands and feet from the rest of the body. I place the pieces into wire mesh containers inside the dermestid colony, and then begin documenting. I take all the important information from the package the animal was in and transfer it into an excel spreadsheet, and make sure to label what specimen is inside the colony. I then clean up my area, and wait around a week before starting the process all over again!

My role in the lab is very important to the success of the dermestid beetle colony, as I skin the lemurs that the beetles eat. But, you may be confused as to what it’s like to skin an animal. First, it’s super interesting to do, as I get to see first hand what differences there are between species. I get experience working with the tools of the lab, and I observe the behaviors of the dermestid beetles. The beetles have tiny minds that control their actions, and function as a group, not as individuals. Sometimes, the beetles may eat a certain part of the body first, and that may tell us something about the quality of meat, or maybe the bugs’ preference. On occasion, a lemur may be a little stinkier than others, but it all depends on the individual lemur. The skin is relatively easy to remove, and requires a steady hand and a scalpel blade. There may be some scent pockets, which may have liquid in them. It tells us more about how that organism lived, and what it ate, drank, or enjoyed doing. The experience after the beetles are done with a body is strange, as I observe how light and fragile a lemur’s bones are. They have many similarities to humans, but many differences. There’s a lot to be learned from observation, and a lot more to be gained.

Alice watering the dermestid colony.

So, how do you find a lab that’s a good fit? The answer: it’s all about searching for your own interests. If you’re interested in dissection and taking care of a colony of dermestid beetles, like I was, you may get lucky and a lab finds you. But for some, it may not be that easy, and that’s okay. Your lab should be a place where you always feel safe, informed, and surrounded by people you can ask for help. In my lab, I have people I trust, that I can count on, with resources and friendly faces all around. You should feel connected and compelled to gain knowledge, and be excited about what you’re doing.

Alice hard at work preparing to feed the beetles.

It may be hard to find a lab, but do not give up! For me, I was in my Introduction to Biological Anthropology class, and my professor (Terhune lab PhD student Caitlin Yoakum) asked the class if anyone would be interested in working in a lab, helping her out. I had already expressed some interest to close friends about finding opportunities in the field. I applied with the professor and did an interview with the head of the lab, and found my home.

Overall, I am definitely glad I began working in my lab, and I would highly recommend following opportunities where you see them. Working in a lab is not only a great experience to have in the moment, but also an extraordinary resource in the future. So, in conclusion: join a lab! Learn something new and exciting! And make sure that you write it down.

Editor’s note: If you aren’t lucky enough to hear an advert for lab work like Alice was, don’t be afraid to seek out opportunities and contact professors or graduate students who are working on things that interest you! Sometimes you will find a lab this is a great fit, and other times you might end up in a lab that isn’t as great of a fit, but you can always learn from those experiences. -Dr. Terhune